Focus on … DED definition and classification

Definition and classification of dry eye disease

TFOS most recently updated the definition of dry eye disease in the DEWSII report of 2017 as:

“…a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterised by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.“5

But why is it so important to have such a definition?

The term multifactorial recognises complexity in that it cannot take a single process, sign or symptom in order to characterize the disorder.

The term disease is important as it recognises the significance of the disorder as a loss of structure or function resulting in signs and symptoms with pathologic and quality of life implications.

Ocular surface here refers to the structures of the eye and adnexa, including the cornea, conjunctiva, lids and lashes, the tear film and lacrimal apparatus.

Homeostasis describes the balanced state in the body of various functions and here relates to the equilibrium of a stable tear film. The loss of this homeostasis is considered to be the main characteristic bringing together the various tear film and ocular surface imbalances seen in the development of DED.

This also defines DED as displaying signs and the sufferer having symptoms. At the core of the disease is a state of hyperosmolarity, induced by tear evaporation.

Etiological roles recognises that these various triggers are linked to the vicious cycle of DED.

Definition is therefore vital because without proper definition, there can be no diagnosis, without diagnosis there can be no patient management, treatment, and from a patient’s perspective, no end point, or at least journey towards an improvement in quality of life.

In classifying DED it is now understood that the scheme should be based on the co-existence of the states of aqueous deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye (EDE) and the elements of these are integral to the diagnosis and management of the disease.

Classifying DED is the way that we can navigate the journey from diagnosis to management. We will concentrate on the beginning and the end of this pathway, which is where the DO has the greatest likelihood of being involved.

Pathway for Classification

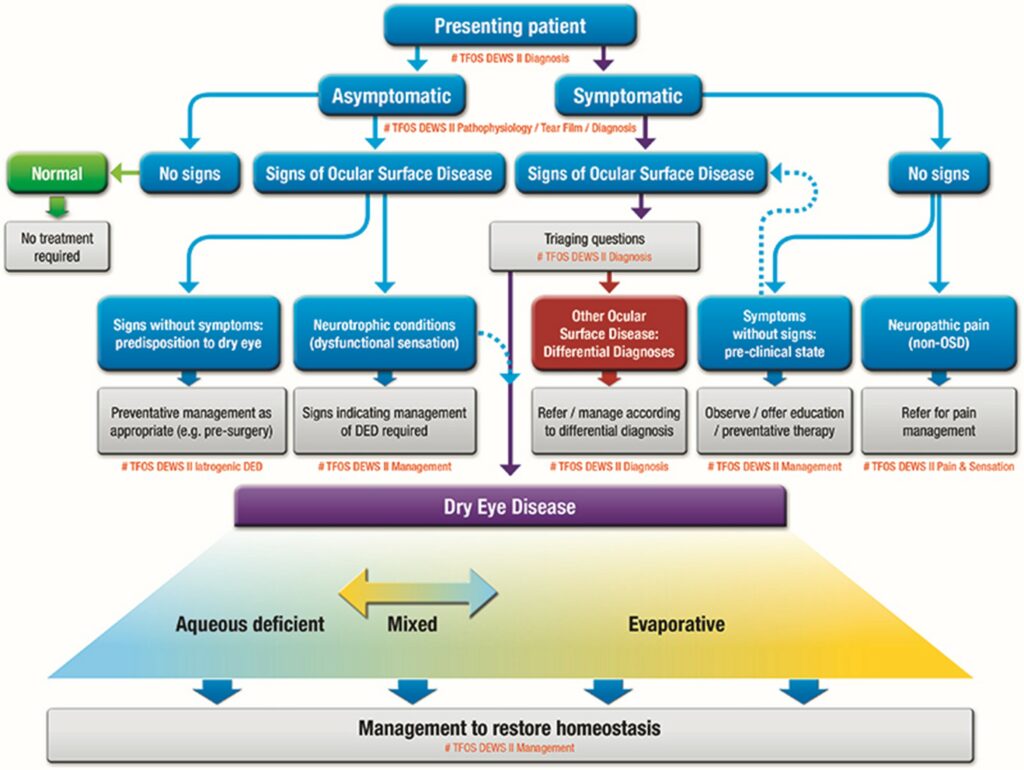

One of the many useful illustrations and flowcharts created by TFOS in the DEWSII report is the pathway for classification of DED (Fig1)5, which helps to distinguish DED from other presenting forms of ocular surface disease (OSD).

It is acknowledged that not all signs and symptoms of dry eye will lead to a positive diagnosis of DED, in fact there is only one of these possible pathways which will confirm DED as previously defined.

Here we will limit attention to the positive diagnostic pathway of symptoms and signs being present.

The careful use of triaging questions and assessment of risk factors will enable differentiation from other forms of OSD and on to appropriate etiological sub-classification and ultimately the most appropriate management.

It can be seen from the lower segment of figure 1 that the two predominant sub-classifications are Evaporative Dry Eye (EDE) and Aqueous Deficient Dry Eye (ADDE) and that they are not mutually exclusive. Evidence shows that although there is a greater proportion of DED classified as EDE, it is more likely, as the condition progresses, that evidence of both EDE and ADDE will be clinically apparent, i.e. mixed dry eye, with 86 per cent of dry eye patients exhibiting signs and symptoms relating to EDE or mixed DED6. It will help in practice to bear this in mind when it comes to discussing management of the symptoms.

Fig 1 DED classification scheme.