Business Bites: Problem? Don’t blame me (Part 1)

“Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new” – Albert Einstein

In the first part of this article, we take a look at problem solving and the associated ‘blame game’ that sometimes holds businesses back.

Blame culture

Don’t get caught up in the ‘blame game’

A blame culture is one in which people are blamed for mistakes. This leads to an unwillingness to take risks or to accept responsibility for mistakes due to a fear of being blamed, criticised or even prosecuted. A good way to detect a blame culture is to think about what happens when a leader detects a mistake. If they ask ‘who?’, rather than ‘what?’ or ‘how?’, this may be evidence of a blame culture.

A blame culture contrasts with a culture in which mistakes are owned, the problem leading to a mistake is identified and improvements made, and people learn from the experience.

In his book, The Blame Game, Dattner offers some approaches that may help you to minimise a culture of blame: “Too often, people and organizations get caught up in ‘the blame game’ and the wrong people get blamed for the wrong reasons at the wrong time. The result can be that people are demotivated and demoralized, focus more on organizational politics than on getting the job done, and are too afraid to speak up or experiment with new approaches.

In their article, ‘Managing yourself. Can you handle failure?’, published in the Harvard Business Review, Dattner and Hogan argue: “Personality psychology provides a research-based behavioural science framework for identifying and analysing how people respond to failure and assign blame. Using data on several hundred thousand managers from every industry sector, we have identified personality types likely to have dysfunctional reactions to failure.

“These include:

- The Sceptical type, who is very smart about people and office politics but overly sensitive to criticism and always on the lookout for betrayal

- The Bold type, who thinks in grandiose terms, is frequently in error but never in doubt, and refuses to acknowledge their mistakes, which then snowball

- The Diligent type, who is hardworking and detail oriented, with very high standards for themselves and others, but also a micromanaging control freak who infantilises and alienates subordinates.

“The underlying theme of our research is that many managers perceive and react to failure inappropriately and therefore have trouble learning from it—leading to more failures down the road.”

Fortunately, managers at all levels of organisations, and at any stage of their careers, can fix their flawed responses to failure.

Self-awareness

You can, of course, utilise one of the many personality tests available. You may also benefit from reflecting on challenging events or jobs in your career, considering how you handled them and what you could have done better. You might ask trusted colleagues, mentors or coaches to evaluate your reactions to, and explanations for, failures.

Pay close attention to how people respond to you in common workplace situations, and ask for formal or informal 360˚ feedback; you might be surprised at what you discover.

As part of self-awareness, one can also consider the question: ‘How am I the issue here?’ A great read on this subject is Leadership and Self-Deception by the Arbinger Institute. The book describes how self-deception makes us blind to all possible solutions to a problem – leading to some poor decisions. It also tells us how self-deception obscures our view of ourselves and our situation, as well as distorting our view of others. It inhibits our ability to make wise and helpful decisions.

Kirton’s adaption-innovation model

Awareness of others preferences

Understanding each other’s cognitive styles, and having an individual who can encourage collaboration between different personalities, is crucial to resolving conflict in problem-solving situations and building creativity.

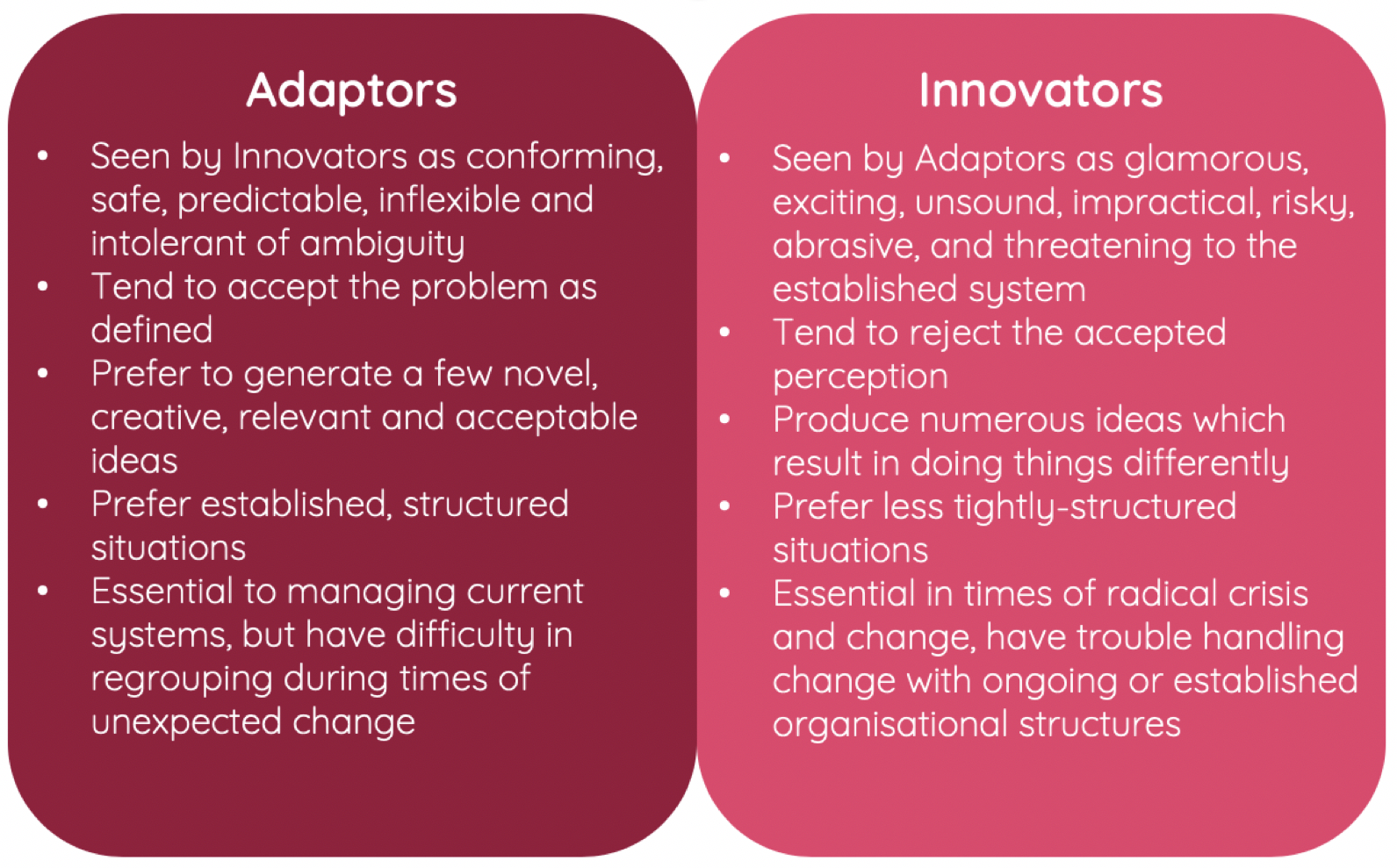

In his book, Adaption-Innovation. In the Context of Diversity and Change, Kirton describes his adaption-innovation (A-I) theory, which groups individuals by their style preference towards decision making, problem solving and creativity. A-I is a cognitive style, which is the preferred manner of bringing about change adopted by individuals. Kirton’s A-I model views these styles as a continuum.

Individuals demonstrate preferences towards being more adaptive and agents of stability, or more innovative and agents of change in their approach to problem solving, decision making and creativity.

This article has looked at blame as an issue in problem solving. In part two, we will look more at the problem solving process.