Evidence-based practice Part 4

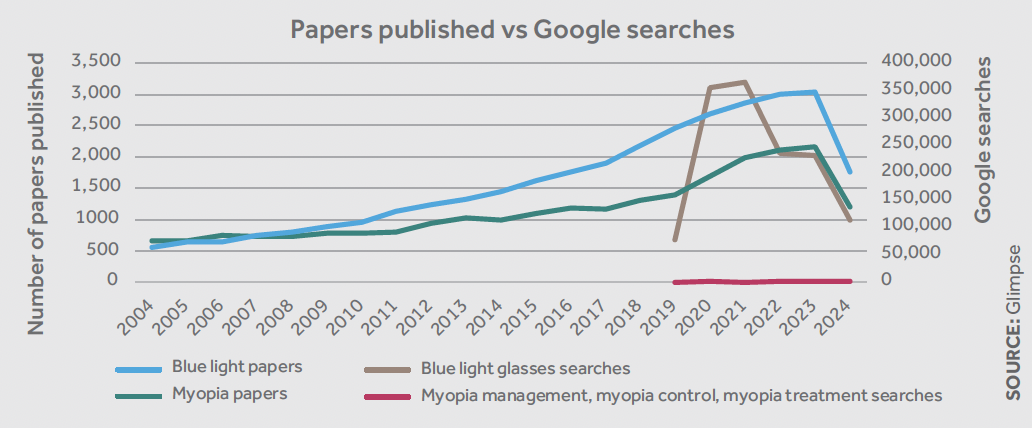

Myopia and myopia management have gained popularity as ‘hot topics’ within the industry in recent years – as demonstrated by the considerable increase in research conducted in this field.

According to PubMed, between 2004 and 2023, papers referencing myopia increased by 230 per cent1; those referencing myopia management increased by 197 per cent2 in the same period.

However, a focus group-based study involving both optometrists and dispensing opticians (DOs) published in 2024 found that for UK practitioners, there was huge disparity in levels of engagement in this emerging field3. Although most practitioners who participated in the study felt they had sufficient knowledge, three key areas of barriers to treatment were identified.

These fell under the following categories:

1. Practice barriers: for example, lack of equipment, perceived low demand for the service.

2. Parental barriers: for example, poor public awareness, affordability.

3. Eyecare practitioner (ECP) barriers: for example, lack of sufficient UK-based evidence, lack of confidence in communicating appropriate information, and scepticism over manufacturers’ claims.

The Coverdale et al paper3 posited that while other studies, such as McCrann et al4, highlighted a lack of knowledge as the main barrier within the profession, their results did not support this; confidence and lack of experience were the main barriers from an ECP perspective.

Both the College of Optometrists5 and ABDO6 have guidelines on myopia management and the role of professionals in delivering suitable advice and care in this field. The ABDO guidance states that: “Dispensing opticians have a duty of care to ensure that they, as individual registrants, supply myopia management advice and guidance in a timely manner, including checking the understanding of and options for the patient concerned, and where appropriate, suppling the appropriate optical appliance. It is important to recognise that myopia management is an interprofessional treatment option and not a one-off dispense. If a registrant is situated in a practice where myopia management options are not available then they should as a matter of course refer patients to a suitably qualified colleague elsewhere”.

While guidance and clinical information on myopia management is readily available, the provision of more practical advice on implementing strategies is less so. Before addressing this, it is worth looking at the data around public awareness.

Public awareness and interest

Public awareness and interest

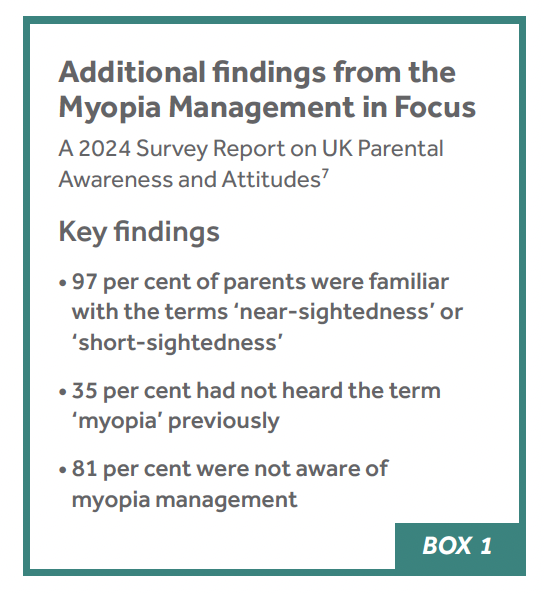

In June 2024, two papers were published concerning public awareness and attitudes to myopia and myopia management. The first study7 sought to identify the level of awareness of myopia management among parents, concluding and that overall it was low even among those with myopic children (of these 70 per cent were unfamiliar with the term myopia management). Of those who were aware of myopia management, 72 per cent reported they had received the information from their optometrist. Where did the other 28 per cent garner information from?

The second study8 used Google Trends data to analyse the global level of interest in myopic progression, tracking the popularity of terms including ‘childhood myopia’, ‘myopia progression’ and ‘myopia control’ finding a steady increase in the last 10 years. While this information is useful, it should be noted that this paper has limitations, in that it includes global data rather than UK specific trends. Additionally, the analysis was performed on ‘interest over time’ (a measure of popularity) rather than on number of searches performed.

UK interest in myopia

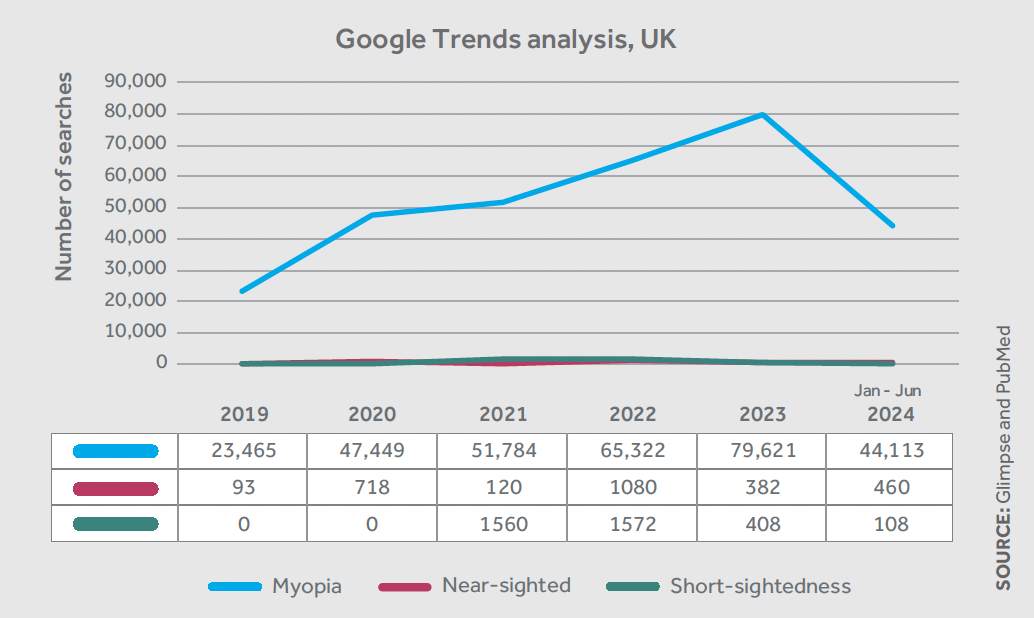

According to Statista9, as a search engine Google has a 93.61 per cent market share in the UK. It is, therefore, a reputable source to analyse what topics the public are interested in. Rather than analysing by popularity, it is possible to use platforms such as Glimpse to analyse search volume over time for keywords with comparisons to others.

Figure 1 shows the number of searches over time for ‘myopia’*, ‘nearsighted’ and ‘short-sightedness’ over the period 2019 to June 2024. Contrary to the findings in the Myopia Management in Focus survey highlighted in Box 1 (which had a small sample size)7, it appears that the public is more likely to search for information using the term ‘myopia’ than any other. This should serve as a guide for the most appropriate terminology to use with patients and parents.

Figure 1: Google searches for various terms relating to myopia

Comparing this to another topic that has been garnering interest in recent years, with a similar trend in published research, we see that myopia treatments appear to be of lower interest to the public than ‘blue light glasses’ (Figure 2). This is despite a Cochrane Review published in 202310, which cast doubt over the validity of many of the claims made about blue light.

Practical implementation

The data comparing myopia to blue light highlights the lack of awareness by the public around valid ocular health concerns. Rather than focusing solely on emerging or existing myopic children, it may be more helpful to take a more comprehensive approach and re-think children’s eyecare as a whole.

The Myopia Management in Focus survey on parent awareness7 found that 40 per cent of the sample (200 parents) did not take their children for an annual eye examination, with 18 per cent stating they rarely or never took their children for a sight test.

While engaging with local schools, children’s clubs (e.g. sports clubs, the Scout Movement) or even conducting advertising campaigns could improve engagement in this area, we can also take steps in practice to support paediatric patients in understanding the importance of regular eye appointments, the type of lifestyle changes that can support better eye health, and the solutions available for those requiring treatment/correction.

Figure 2: Published papers on myopia and blue light 2004 to June 2024, compared to Google (UK) searches for blue light glasses and myopia solutions

A conversation about a treatment plan, which may involve a higher cost solution, may be more comfortable if the previous visits have included additional clinical advice on areas such as blue light from screens, and UV protection (even for those who do not require prescription eyewear). Also, perhaps, a conversation about anti-reflection coatings for those requiring correction, rather than assuming that the only interest for both parent and patient is in ‘free’ spectacles.

Conclusion

Children have traditionally been a relatively minor part of optometric practice with the majority of complex cases being dealt with by ophthalmologists and orthoptists. The advent of novel myopia management solutions highlights the key clinical role DOs play within a practice, giving an opportunity to improve all paediatric eyecare from the dispensing desk.

If, like those surveyed in the Myopia Management in Focus project7, you lack confidence in recommending additional cost solutions to those who have traditionally been supplied with solely NHS funded care – or if you find it difficult to discuss potential health risks of progressing myopia – consider starting small. Offer advice to parents on all aspects of their child’s eye health – from screens to outdoor time – to gain confidence in your skills as a clinician.

As a profession, perhaps we can switch searches for ‘blue light glasses’ to terms such as ‘UV protection’, ‘Child eye health’ and ‘Where can I find my local dispensing optician?’.

* The term ‘myopia’ rather than ‘childhood myopia’ or ‘myopia in childhood’ was used as these terms have negligible search volumes in the UK.

Eluned ‘Lil’ Creighton-Sims FBDO is a dispensing optician and education and professional development manager for IOT Lenses.

References

1. National Library of Medicine (PubMed): Myopia. [Accessed 10 July 2024].

2. National Library of Medicine (PubMed): Myopia Management. [Accessed 10 July 2024].

3. Coverdale S, Rountree L, Webber K, Cufflin M, Mallen E, Alderson A et al. Eyecare practitioner perspectives and attitudes towards myopia and myopia management in the UK. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024 Jan. 11;9:1.

4. McCrann S, Flitcroft I, Loughman J. Is optometry ready for myopia control? Education and other barriers to the treatment of myopia. HRB Open Res. 2019 Nov. 15;2:30.

5. College of Optometrists. Childhood-onset Myopia Management: Guidance for Optometrists 2022. [Accessed 10 July 2024].

6. Association of British Dispensing Opticians. An Overview of Myopia Management. [Accessed 10 July 2024].

7. Higginbotham J, Kadri-Langford R, Ghorbani MJ. Myopia Management in Focus: A 2024 Survey Report on UK Parental Awareness and Attitudes. Available from: www.myopiafocus.org/awareness

8. Panneerselvam S, Diklich N, Tijerina J, Falcone MM, Cavuoto KM. Can Google help your nearsightedness? A Google Trend analysis of public interest in myopic progression. Clinical Ophthalmology 2024;18:1771-7.

9. Statista. Market share of leading search engines in the UK in March 2024. [Accessed 9 July 2024].

10. Singh S, Keller PR, Busija L, McMillan P, Makrai E, Lawrenson JG et al. Blue-light filtering spectacle lenses for visual performance, sleep, and macular health in adults. Vol. 2023. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2023.

This article first appeared in print in the September 2024 issue of Dispensing Optics.